Reflections on the Reconstruction

Tuesday, March 26, 2013 at 03:06PM

Tuesday, March 26, 2013 at 03:06PM Port-au-Prince, HAITI 26 March 2013 – Haitian and international media have published many articles on the progress of Haiti’s reconstruction.

The watchdog partnership Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) has been investigating this subject, in depth, for almost three years now. For a change, HGW decided to approach some of the major players to inquire about the following three aspects of the reconstruction process.

1) Aid, dependence and sovereignty

2) The Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC)

3) The question of vision, leadership and coordination

HGW made numerous requests for interviews, several of which were refused, namely those with government ministers and several members of parliament [1]. Nonetheless, HGW was able to access numerous national and international actors important to the reconstruction, such as: four former members of the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC), three current and former employees of the Haitian government, and the Haitian representatives of the World Bank (WB), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Cover photo - a resident digs a hole at the Tabarre Issa camp. Read more here.

Photo: Fritznelson Fortuné

Aid and dependence, sovereignty

Well before the 12 January 2010 earthquake, Haiti depended largely on international aid to finance its government projects, programs and budget. Bilateral and multilateral donor funds were far more important than the internal revenue of the Haitian government.

The earthquake largely exacerbated this situation.

Post-earthquake international aid to Haiti falls into two categories: emergency aid, concentrated on humanitarian aid, and reconstruction aid to finance rebuilding and long-term development. Much like aid to Haiti before the earthquake, the majority of this money bypassed the Haitian government and ended up directly in the hands of private contractors, “NGOs” or “Non Governmental Organizations”, bilateral and multilateral agencies and other non-state actors.

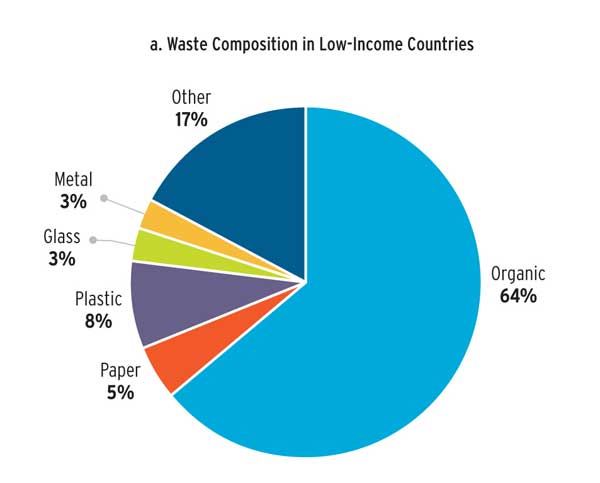

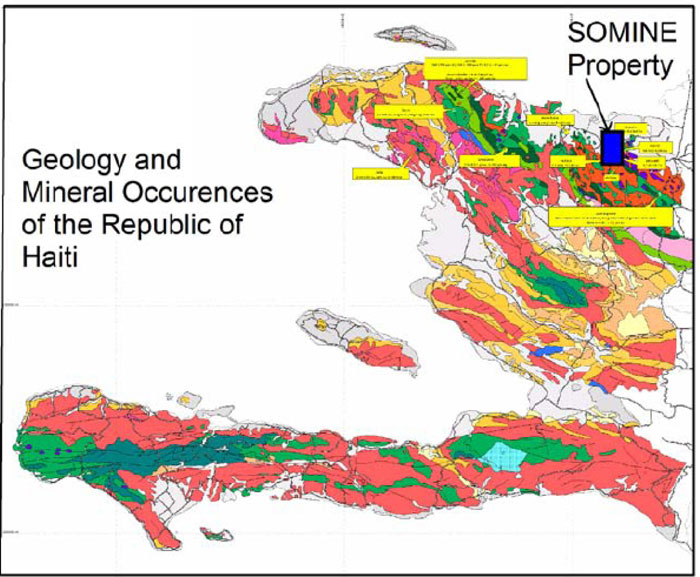

Graph showing the amount of reconstruction assistance that went to the Haitian

government (dark blue).

Source: Office of the UN Special Envoy for Haiti - "Has Aid Changed?" [PDF]

Only one percent of emergency aid went to the Haitian government. The figures were slightly higher for reconstruction money: bilateral and multilateral donors respectively gave seven and 23 percent of their money to the Haitian government.

What do those interviewed think?

Michèle Oriol is executive director of the Interministerial Committee for Territorial Planning (CIAT in French), a government agency in charge of coordinating the actions of six (6) ministries.

“We need to do a kind of global reflection on the question of international aid. My impression is that international aid throughout the world doesn’t reap much success,” she noted.

And, she emphasized, “Who votes for it? It isn’t foreigners who vote in our place in their home countries to then come and impose it on us. We must first question the responsibility of Haitian authorities about the financing and functioning of the Haitian state and not the other way around. The responsibility is first and foremost a national one.”

Jacques Bougha-Hagbe is an economist and engineer by training. He has represented the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Haiti since March 2010.

“We can’t deny it. A substantial part of the aid does not go through the Haitian government and we find this deplorable, also. I don’t think it helps to simply blame the donors, because Haiti is a sovereign country. What is stopping the government from assuring there are structures that inspire confidence?

“Ideally, we would have made funds available to the Haitian government and the government would have used these wisely while staying accountable to the Haitian population and the partners,” he added, remarking that, “I don’t think things will succeed unless the government proves it has a leadership in which donors can trust. Because, in the end, no one will ever be able to replace the government.”

For Bougha-Hagbe, even a weak Haitian government must try to play its role: “Certainly the Haitian government has weaknesses, but it has the last word... The principle donors may be NGOs, but they can’t carry out anything without the approval of the government.”

The IMF representative ended by saying: “Haiti is a sovereign country. The day the Haitian government asks me to leave the country, I will leave, because they are the bosses. The IMF cannot impose anything at all on Haiti... The Haitian authorities themselves must absolutely make the necessary reforms... [and] increase the revenue of the state and [thus] make the country less dependent of foreign assistance.

A view of a typical “cluster” meeting meant to coordinate emergency

response. For months, almost all meetings were run in English only,

and many had no Haitian government presence. Read more here.

Michel Présumé is director of the public buildings division at the Control Unit for Public Housing and Buildings (UCLBP), a small government agency.

Présumé noted that he likes to be realistic or at least pragmatic and said: “It’s clear that our means are very weak and our needs are enormous... We are weak because we don’t have the means to do what we want. At the moment we’re waiting for the aid of others, but it gets to a point where it’s almost painful.”

Présumé, a civil engineer and former employee of the Ministry of Public Works for 13 years, thinks that there are certain delays in the disbursement of money “because there’s a will to take back control. That explains the delay in aid.”

“A lot of reports refer to the percentage of the aid that goes to the Haitian government. We must change this. The only means of getting there is to become a more responsible and respectable country,” he concluded.

Jean Claude Lebrun has been the national coordinator of Movement of Independent Integrated Organizations and of Engaged Unions (MOISE) since 13 November 2006 and is former member of the IHRC, where he represented the union sector.

“The United States had control over everything that was being done in the reconstruction. This stranglehold was exercised through different entities and also through the influence of the Clinton Foundation, which was very active in reconstruction-related decisions.”

Lebrun is convinced “an absence of leadership” drove the country into its current position of dependency. “We cannot reestablish sovereignty through international aid,” he said.

Alexandre V. Abrantes has been a doctor and health administrator at the World Bank (WB) for the past 20 years and is currently the bank's representative in Haiti.

“The government had control over decisions made about reconstruction, at least while the IHRC was still operating.”

Almeida Eduardo Marquez was the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) representative in Haiti during the earthquake and post-quake period. He was interviewed via email.

Marquez noted that “the Haitian state’s weak executive capacity existed before the earthquake.”

William Kénel-Pierre is an architect and founding member of the political party Organization of People in Struggle (OPL).

“If I were to speak about reconstruction, I would start by speaking about the need to reconstruct our sovereignty, our dignity and our social structure. I can’t speak of reconstructing our social structure so much as of building a new social structure that can change the situation in which we are living,” he said.

For the Kénel-Pierre, foreign assistance is always synonymous with obligations. About the IMF, he wondered, “Is their mission to assist us or to manage the money they are lending to us?”

“Before the earthquake, it was clear that out institutions were in a serious state of collapse. The earthquake transformed that into what can be described as an ‘epiphenomenon’ of our general and more serious problems.”

New slum on Morne L'Hôpital, comprised mainly of T-Shelters donated by NGOs.

Read more here. Photo: HGW / Evens Louis

Jean-Marie Bourjolly is a mathematician and a professor at the School of Sciences and Administration at the University of Quebec in Montreal. Bourjolly was a member of the IHRC, from July 2010 to July 2011, as a representative of the executive power. Bourjolly is also editor of the review Haiti Perspectives. He was interviewed via email.

“We owe the extent of our troubles most to the chronic weakness of the Haitian state, and to the laissez-faire and lack of vision of our leaders,” according to Bourjolly, who has published the entirety of the interview with HGW in Haiti Perspectives.

The professor blamed “the weakness of the state and deficient leadership that manifests itself in the proverbial kleptomania of Haitian leaders, too inclined, as we know, to confuse their personal coffers with the national bank accounts, and their personal interests with those of their country.”

“The Haitian state, weak as it was before the earthquake, became bloodless and poly-traumatized; for their part, over the years the NGOs constituted themselves into a state within a state wherein the label 'Republic of NGOs' gained currency as Haiti’s nickname. As for entities like the World Bank, the IDB, and USAID, they were not in the habit of telling us about their activities and it’s hard to see what could have been done to change their approach,” he added.

Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC)

The IHRC was created by a presidential decree on April 21 2010. According to the decree, its role was “strategic planning, coordination, project development, rapid and efficient implementation, use of resources, project approval, optimization of investments and contributions, and technical assistance.”

Jacques Bougha-Hagbe, IMF representative.

“Why did we create the IHRC? To be honest, it’s because there is still this lack of confidence between many partners and the Haitian government.

“The idea of the IHRC was interesting at first. It initially created a forum that allowed the partners as well as Haitian civil society to see together how they could move forward,” he noted. “Unfortunately, the institution encountered problems that many other aid coordination platforms have known. Harmonization between practices and objectives of the partners and the government is crucial, but it is hard to establish.”

The IMF representative thinks that the challenges faced by the IHRC were not specific to Haiti, because “the difficulties it faced simply reflected the difficulties of aid coordination in developing countries in general.”

For Bougha-Hagbe, even if the IHRC mechanism was new and no longer exists, “there is always a disguised IHRC in Haiti. It’s the aid coordination mechanism... that rests on ‘sectorial tables.’ Sectorial tables are sector subgroups between the donors and the government that discuss strategy in the domains of education, health, sanitation, security and governance.”

One of the drawings for the reconconstruction of Port-au-Prince, proposed by the Prince

Charles Foundation of the UK. Read more here. Source: Prince Charles Foundation

Jean Claude Lebrun, former IHRC member.

“The biggest weakness of the IHRC was its problem with communication...The IHRC functioned in closed circuit and no information was let out.

“The IHRC could have been better if it have been more democratic and if… information had circulated freely. There was a information deficit,” he added. “Only the executive committee and the executive secretariat made the decisions... the executive committee had two co-presidents: Bill Clinton and Jean-Max Bellerive.”

While the Parliament had representatives within the IHRC, they had no control over it. According to Lebrun, “that was the IHRC’s undoing.”

Furthermore, he added: “Within the IHRC, [some] international representatives also had problems because the only sector with any decision-making power was the pro-American sector.”

Alexandre V. Abrantes, WB representative in Haiti.

“The IHRC was a very good initiative and I completely disagree with all those who criticize it without understanding what it accomplished,” he insisted. “All of our World Bank projects passed through the IHRC.”

“I believe that there was this perception that the IHRC was dominated by foreigners. It was for political reasons, national pride. And as you know, the international press loves telling bad stories. What they do is come after six months to talk about how 'nothing has happened, reconstruction isn't beginning.' It’s ridiculous,” he added.

Almeida Eduardo Marquez, former representative of the IDB in Haiti.

The IDB representative shares the same position as his counterpart at the WB.

“The IHRC was an excellent initiative for coordinating international action with the government and for attracting attention, as much from donors as from the private sector. It would have been more successful if it had been used more as a communication tool between Haiti and the international community," he said.

Like other actors, he thinks that the experience of the IHRC could lead to improvements in other domains such as the “sectorial tables” and the government’s new Coordination for External Assistance for Haitian Development entity (CAED in French) that is supposed to now be in charge of managing of international assistance.

The unused model homes at the failed $2 million housing exposition. Read more here.

Photo: HGW/Jude Stanley Roy

Lucien Bernard is rector of the Episcopal University of Haiti, a professor at the State University of Haiti and former member of the IHRC, where he represented the senate.

“There was no communication. We were kept in the dark about what was going on. Control was in the hands of a bunch of international organizations. Even the document on internal regulations was presented to us in English,” according to the professor. “It was a deliberate attempt to trick us. It’s the same thing most governments do to their people.”

Garry Lissade, a lawyer and head of a well-known firm in the capital, represented the judiciary on the IHRC.

Lissade felt that the IHRC was “a very good thing that could have offered the country a good start for the reconstruction, because the manner in which the interim commission was formed was not unilateral. It was constituted by both national actors and international donors.”

While admitting that the IHRC suffered due to certain challenges, Lissade qualified the experience as a success.

“The IHRC had a particular structure and was a unique model in the world, with the Haitian members designated by the Haitian authorities and members of civil society designating their IHRC representatives. What distinguished the IHRC was that so-called ‘friends of Haiti’ countries did not just hold Haiti’s hand and decide for Haiti. Instead, they sat down with the country at a table,” according to Lissade.

Jean-Marie Bourjolly, professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal and former member of the IHRC.

“In a country where the public authorities were known uphold their responsibilities and work for the common good, a supranational organization like the IHRC would have been, without a doubt, useless and even unthinkable,” according to the professor.

“The creation of the IHRC was preceded by a presentation and publication of two studies, thanks to the initiative, and the technical and financial help of the international community. One was called the ‘Post Disaster Needs Assessment’ (PDNA) to look at the extent of the damage, and the other was the ‘Action Plan for the Recovery and Development of Haiti’ (PARDH in French), published in March 2010 to plan not only the physical reconstruction, but, according to the Head of State, ‘a re-founding of Haiti.’... I think it is in this context that one must see the IHRC. On paper, it seemed to correspond to the situation. I refer to the eight goals referred to in Section 5 of the IHRC’s rules: strategic planning, coordination, project development, rapid and efficient implementation, use of resources, project approval, optimizing investments and contributions, technical assistance.”

However, Bourjolly noted, “The IHRC was a big machine that completely evaded the control of its administrative council” because the council, in his opinion, “had unanimously, minus one voice, voted to give ‘full control’ to its two co-presidents, Mr. Clinton and Mr. Bellerive, who tenaciously and loudly insisted on that, against all reason, until they succeeded.

“The IHRC could have acted as a leader in this resurrection or, at least, it could have obtained much better results if it had opted for transparency both within the commission and toward the outside, and if it had opted to gain the trust of the Haitian people rather than treating them with suspicion,” according to Bourjolly.

Despite all these critiques, the professor contends that, “I sincerely believe, despite the very harsh criticisms I’ve just formulated, that in the circumstances, the role played by the IHRC was positive overall.”

Coordination, Leadership and Vision

According to the accounts of some actors, the earthquake also provided the international community, through its different organizations (such as multinational agencies, donors), the opportunity to exercise greater control over Haiti. While for others, it was an opportunity to prove, in black and white, the lack of leadership and vision of Haiti’s authorities.

There were attempts at coordination. The Action Plan for the Recovery and Development of Haiti (PARDH) was supposed to be the compass for the reconstruction, and for an incalculable number of projects, there were dozens of “clusters” to organize the emergency response, and there were countless conferences, seminars, and round tables. But studies and testimonies complained of the lack of coordination.

Jacques Bougha-Hagbe, representative of the IMF.

Bougha-Hagbe noted that it is always difficult to coordinate post-disaster aid in a poor country.

“The general problem is that, on the one side, you have the government who must continue to play its role, and [on the other], the international donors who have their own realities,” he told HGW.

However, a government cannot just give up. It must accept to rise to the challenge, he added.

“The government must always maintain leadership over the development strategy. But its leadership must be enlightened, clear and confidence inspiring. I don’t believe anything will succeed until the leadership can gain donor trust. Because no instance can ever take the place of the government,” he added.

“The ideal would have been for the government itself to have developed the mechanisms to distribute donor aid. But the mechanisms must be reliable. That means that if a donor decides to make resources available to the government, the government will use the resources to carry out the agreed upon objectives,” he concluded.

A map showing and listing the dozens of multilateral, bilaterial and aid organizations

and agencies working on agricultural projects as of September 2010. Source: OCHA

Michel Présumé of the UCLBP.

Présumé, without beating around the bush, admitted: “I do not know who is the real ‘driver’ [of the reconstruction], except that we know our mandate [at the UCLBP] and our mandate is clear. We have had very good collaborations with all institutions and we know what we need to do.”

Alexandre V. Abrantes, WB representative in Haiti.

“The government had the control over reconstruction decision-making, at least during the existence of the IHRC,” according to the WB representative. Abrantes gave as examples the reconstruction of the General Hospital (HUEH) and of National Highway #3.

“The decision was made by the government. The execution... There, you are correct. The government didn’t have control over the execution of these projects, but had the control over the decision to do this or that project,” said Abrantes.

The WB representative said he thinks the Haitian government has today regained power over both the direction and the coordination of the reconstruction.

“Now, with the new document for the Coordination for External Assistance for Haitian Development entity (CAED in French), it’s pretty clear that the Minister of Planning [a position currently held by Prime Minister Lamothe] plays an important role in the coordination of aid.”

Almeida Eduardo Marquez, former IDB representative.

Asked who has control over the reconstruction, Marquez said: “I think the best answer to this question isn’t who has, but rather who should have control. The answer is simple: the government. There is no way to rebuild Haiti without the participation of the Haitians themselves, coordinated by the government. A government capable of creating a plan, targeting projects, managing finances and coordinating, in partnership with the private sector, civil society and the donor governments, in an autonomous and democratic manner, is the only solution for the reconstruction. I see that the necessary provisions have now been made for this to happen.”

Photo collage showing the many kinds of “transitional shelters” built by perhaps

three dozen organizations all over Haiti. Read more here. Source: Shelter Cluster

Jean-Marie Bourjolly, professor and former member of the IHRC.

“The PARDH, I repeat, is a sketch of a plan. I’ll add this: a sketch of a plan concocted quickly by the international community on behalf of the Haitian government, with the participation of the some of the Ministry of Planning staff. The Haitian government then presented it officially to this same international community to make believe it was in control of something, a fiction that fooled no one, certainly not the international community, but which had the effect of dampening certain nationalist criticisms… Even more, it was conceived without the participation of the actors on the ground who were fighting admirably against the multiple post earthquake problems.

“If the reconstruction was to be coordinated, it could not have been done so by anyone other than an organization invested in the mission and the power to decide – in consultation with the legitimate authorities (ministers, NGOs, international community, communities, local authorities and civil society...) – on what needed to be done globally and locally, according to which priorities, with which resources, and to verify or have verified what is being done on the ground in order to be able to rectify problems.”

Houses built and donated by the government of Venezuela which sat empty for 15 months

after the earthquake. Read more here. Photo: HGW/James Alexis

[1] The following people ignored our interview requests, made via letter and in person at least two or three times in each case: the Prime Minister and the Minister of Planning and Foreign Cooperation Laurent S. Lamothe, the Director General of the Ministry of Planning and Foreign Cooperation Yves Robert Jean, the former Executive Director of the IHRC Gabriel Verret, the Special Envoy to the UN Secretary General former US President William J. Clinton and his deputy Dr. Paul Farmer, and the former co-president of the Haiti Reconstruction Fund (HRF) Joseph Leitman.