After Two Bans, Styrofoam Trash Still Plagues Haiti

Tuesday, August 13, 2013 at 08:42PM

Tuesday, August 13, 2013 at 08:42PM Port-au-Prince, HAITI, 13 August 2013 – Despite two decrees making their import and usage illegal, styrofoam cups and plates are used and littered all over the capital, as well as bought and sold, wholesale and retail, completely out in the open.

The first decree, dated August 9, 2012, went into effect on October 1, 2012, as part of a decree that also outlawed “black plastic bags,” used by street vendors (called “ti machann” or “little merchants”) as well as in greenhouses all over the country.

The Environment Minister at that time, Ronald Toussaint, did not sign the 2012 decree, which was announced and lauded by various media and environmental websites as a big step forward for Haiti.

“Because of my experience in this domain, I did not sign the document," Toussaint told Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW). "The concerned parties – the polluters, the importers, and the business people – were not part of its elaboration. The government’s decree offered a very reductionist approach to dealing with plastic waste.”

Styrofoam containers for sale on August 6, 2013, on a street

in Pétion-ville, Haiti. Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

In spite of the obvious failure of the 2012 decree, the government of President Michel Martelly and Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe recently adopted a new one, dated July 10, 2013 and written in much the same language.

There is an “interdiction on producing, importing, commercializing, and using, in any form whatsoever, plastic bags and objects made of styrofoam for food purposes, such as trays, bottles, bags, cups, and plates,” according to the July 10 issue of the government's official journal of record, Le Moniteur.

“As soon as this decree becomes applicable, beginning on August 1, 2013, all arriving packages that contain these objects will be confiscated by customs authorities and the owners will be sanctioned according to customs regulations,” the decree reads.

In addition to being a bit demagogic in nature – given that the first decree was completely ignored – the new decree has also angered the Dominican Republic's industries, Haiti’s principal suppliers of styrofoam plates and cups for take-out food.

A package of 100 styrofoam containers from the Dominican Republic.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

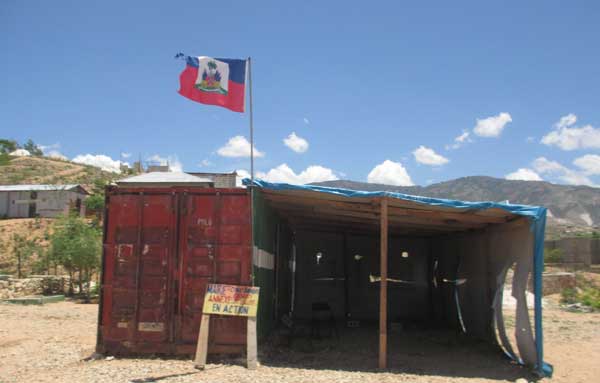

A Sea of Styrofoam

If the last ten months are any indication, there is little reason to think the new decree will bring about any change. The streets of the capital region are awash in styrofoam. Any passerby, police officer, or state official can see bright white products, as well as the illegal black plastic bags, being used and discarded everywhere.

Plastic trash can be catastrophic for the environment. In addition to clogging drains and causing flooding, rivers and then sea currents carry the trash all over the world.

One of the many drainage canals in the Port-au-Prince metropolitain area.

Most dump into the Caribbean Sea after passing through poor neighborhoods,

like this one in Cité Soleil, where the human and animal fecal matter, styrofoam,

and other trash regularly flood the zone after heavy rains.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

“Plastic trash is a real problem, in my opinion,” Toussaint said. “It is a sanitation problem and a public health problem. It is also a problem because of the damage it causes to coral and marine ecosystems.”

Because Haiti has not worked out a way to deal with styrofoam and plastic trash, some people solve the problem themselves via incineration. Speaking to AlterPresse in 2003, the head of environmental group Fédération des Amis de la Nature (Federation of Friends of Nature) spoke about plastic’s toxicity.

“Plastic is a synthetic produce made of chemicals like oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon,” said Pierre Chauvet Fils on June 12, 2003. “Incineration or burning plastic has serious consequences on the natural environment. The smoke produced is very toxic.”

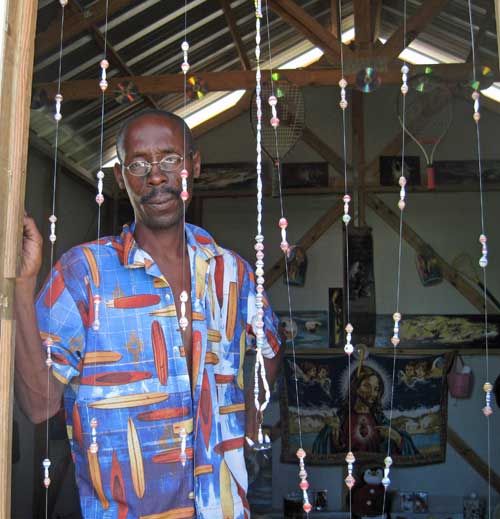

Easy to see and to buy

In spite of its dangers, and in spite of the two decrees, styrofoam products are everywhere.

An investigation by HGW in downtown Port-au-Prince and in Pétion-ville in May and June 2013 found that almost all of the street-food vendors were using the illegal products. Downtown, on four streets studies, 28 of 28 vendors – 100 percent – used styrofoam dishes and cups. In six streets of Pétion-ville, journalists tallied 20 of 26 vendors – 77 percent – using the illegal products. A visit last week, after the new decree went into effect, revealed that nothing had changed.

A typical meal on the run in Petion-ville, Haiti, on July 25, 2013.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

Two very popular Pétion-ville restaurants, Contigo Bar Resto Club et Mac Epi, were also using styrofoam products, both before and after August 1.

And many – perhaps even all – of the nearly a dozen franchises and restaurants of the popular Epi d'Or chain, owned by Thierry Attié, use styrofoam take-out containers. Many also use styrofoam cups and styrofoam plates for those "eating in." (HGW was not able to check all of its many locations.)

A meal in a take-out container at one of Epi d’Or’s many restaurants. This one is

in Delmas, Haiti. Diners eating in are often given styrofoam plates instead of

styrofoam “clamshells.” Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

On its website, Epi d'Or says it works "with strict respect for laws and for the public interest."

Asked via email why the chain has been using the products, which have been illegal for over ten months, Attié responded that his outlets had replaced the cups but not the “clamshells.” However, HGW observed styrofoam cups in use at Epi d’Or’s Pétion-ville outlet on August 9, the day of Mr. Attié’s message.

“We're in the process of getting rid of all Styrofoam products,” Attié wrote. “My desk is full of samples from all over, but I have yet to find an alternative to Styrofoam that will work with my low prices.”

It is not difficult to buy styrofoam products wholesale. Of 11 food and general supply stores or stands visited in June and July, ten openly sold the illegal products. On August 5, five days after the new decree made the “trays, bottles, bags, cups, and plates” illegal for a second time, these products were for sale almost everywhere they had been earlier in the summer.

Speaking in June, one businessman told HGW that nobody really paid attention to the first degree.

“The ban was not applied," said the merchant while working at his store on Rue Rigaud. "We heard about it on the radio.” (The HGW journalist did not reveal his identity and instead pretended to be a client. He did not ask most businesspeople for their names, but HGW has meticulous records of the stores visited.)

A delivery in Pétion-ville. Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

A businesswoman supervising a team unloading merchandise from a truck at her Rue Rigaud store told HGW, as did at least two other businesspeople, that she bought her styrofoam products at SHODECOSA, one of the city’s industrial parks housing assembly industries which receives regular deliveries from the Dominican Republic in big container trucks.

SHODECOSA (Superior Housing Development Corporation S.A.) is the country’s biggest private industrial part. It belongs to the WIN Group, the conglomerate owned by the Mevs family, which also has interests in maritime transport, assembly industries, and ethanol. WIN also runs the country’s largest private port, TEVASA, in the Varreux area of Cité Soleil.

“Ever since Lamothe became prime minister, I stopped going to the Haitian-Dominican border because only the bourgeois have the containers that are authorized to cross the border with merchandise,” the businesswoman claimed.

A Rue Geffard businessman said he buys a “packet” of 200 styrofoam plates for 575 gourdes (US$ 13.37) and resells it for 650 gourdes ($US 15.12).

“It is not easy to import plates,” he said. “You have to work really hard to get them at SHODECOSA for an exorbitant price.”

Another wholesaler on Rue Rigaud said he buys at SHODECOSA and also buys them by the container at the border towns Elias Pinas and Malpasse.

HGW did not speak with WIN Group about the allegations. However, the fact that various Pétion-Ville store told matching stories about where they got their products indicates that during the ten months of the first decree, and perhaps still, styrofoam plates, cups, and other items were for sale somewhere inside the park.

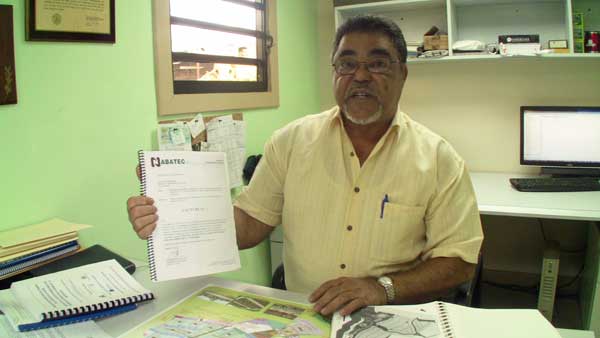

New Decree, New Anger

The new decree banning plastic and styrofoam products angered many businesspeople and associations in the Dominican Republic. It came just a few weeks after the Haitian government announced a ban on certain Dominican products on Jun. 6, 2013, supposedly in order to protect Haitians from avian flu (H5N1).

Dominican authorities maintained that their country had no cases of H5N1, only influenza A (H1N1). Dominican chickens and eggs were blocked for over a month but now appear to be crossing the border without problem. Much of the chicken and most of the eggs consumed in Haiti come from her neighbor. [See HGW Dossier 24].

Immediately after the anti-plastic and anti-styrofoam decree, the Asociación de Industrias de la República Dominicana (AIRD or Dominican Republic Industries Association) called on Dominican authorities to defend the national interest. The government statistics agency puts the value of plastics exported to Haiti at US$67.3 million per year, according to Listin Diario.

A package of 200 styrofoam containers from the Dominican Republic.

The label says they are "oxo-biodegradable." Oxo-biodegradable plastics

break down much more quickly than standard plastics.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val.

“We believe the steps taken by Haiti are not those normally taken by two countries that have a trade relationship, and that such acts should be founded on internationally solid and acceptable reasons,” said AIRD president Ligia Bonetti.

Many other Dominican business associations have also denounced the decree.

Quoted in Listin Diario, Sandy Filpo, head of the Asociación de Comerciantes e Industriales de Santiago (Association of Santiago Businesses and Industries) noted that Dominican products are made to international norms.

“It’s clear that [our products] do not have substances that are harmful to health, the way Haiti claims,” he said. “This is all an excuse to try to justify what they are doing to our country.”

The Association of Dominican Exporters says Dominican plastic products are exported to over 70 countries.

A Plastic Decree vs. a Rigid Policy?

In the second decree, the Haitian government promised, “the Ministry of Economy and Finances will take the steps necessary to facilitate the import of inputs, recipients, and paper products or cardboard that are 100% biodegradable such as bags made of fiber or sisal.”

To date, no “steps” have been announced.

In a recent Nouvelliste article, Environment Minister Jean-François Thomas said: “The decree will be applied gradually, in a rigorous and organized manner.”

To date, no confiscation or arrests appear to have been carried out, except to seize the merchandise of wholesalers in the poor neighborhood of Marché Salomon. Restaurants like Epi d'Or and street sellers are still using styrofoam cups and plates that will eventually end up in ravines and canals.

Another law makes tree-cutting illegal, but piles of planks cut from Haitian trees are for sale on city streets all over Haiti. Just like that law, the new anti-plastics decree appears destined to be ignored.

The Martelly government baptized 2013 the “year of the environment.” But Haiti, according to another government slogan, is also “open for business,” which generally means, low or no tariffs, and open borders, at least for merchandise.