Questions about the reconstruction's housing projects

Wednesday, January 8, 2014 at 12:21PM

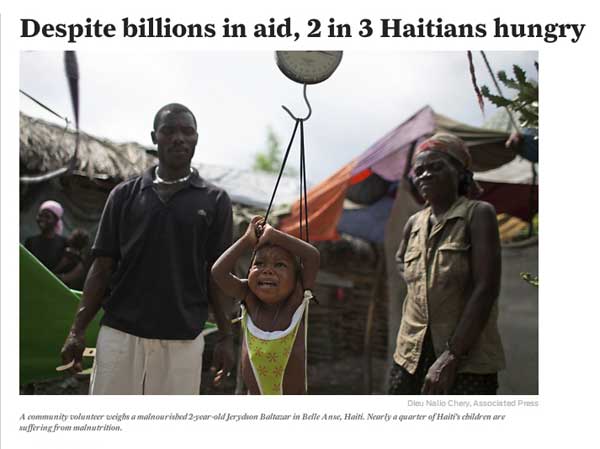

Wednesday, January 8, 2014 at 12:21PM Port-au-Prince, 8 January 2014 – Four years after the January 12 2010 earthquake, questions haunt the four main post-disaster housing projects built by the governments of René Préval and Michel Martelly.

Who lives in them? Who runs them? Can the residents afford the rents or mortgages? Are the residents the earthquake victims?

By some estimates, the catastrophe killed some 200,000 people and made 1.3 million homeless overnight by destroying or damaging 172,000 homes or apartments. But the new projects do not necessarily house earthquake victims, over 200,000 of whom still live in tents or in the three large new slums called Canaan, Onaville and Jerusalem.

In total, the new housing projects, with homes for at least 3,588 families, cost US$ 88 million, according to government figures. (In contrast, international donors and private agencies spent more than five times that amount – about US$ 500 million – on "temporary shelters" or T-shelters.) See HGW #9

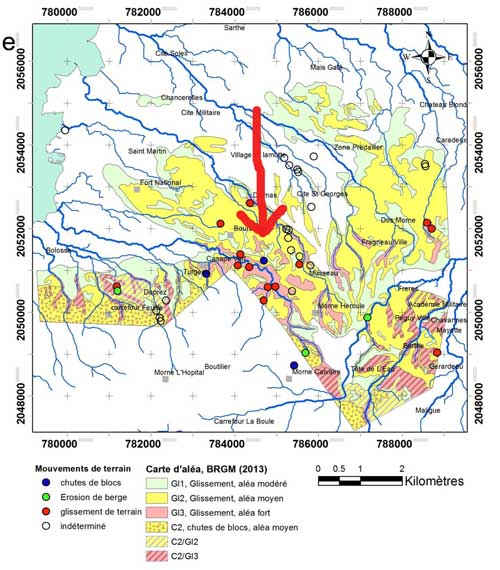

Three of the new housing projects are in Zoranje, a new settlement not far from downtown, on the border between Cité Soleil and Croix des Bouquets. The “Housing Expo” homes sit between the housing constructed by the Venezuelan government and the project known as “400 percent.” (They are also adjacent to an earlier housing project, Renaissaince Village, built by the Jean-Bertrand Aristide government.) The fourth is the Lumane Casimir Village, at the foot of Morne à Cabri, about 25 kilometers north of the capital on the highway that leads to Mirebalais.

An intersection showing mostly empty homes at the heart of the Lumane Casimir

Village near Morne à Cabri on September 19 2013.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

An investigation by Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) involving over 20 interviews and many visits discovered that, even though there are newly housed families, many – probably the majority – are not necessarily victims of the earthquake. Also, several are plagued with lack of services and persistent acts of vandalism, theft and waste.

Clinton’s pet project now home to squatters

On July 21 2011, President Martelly, former US President Bill Clinton and then-Prime Minister Jean Max Bellerive inaugurated the Housing Exposition: a fair featuring about 60 model homes in Zoranje.

One of the first projects approved by the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, the Expo cost over US$ 2 million in public reconstruction money. Foreign and Haitian construction and architecture firms also spent at least US$ 2 million more. The objective was to provide models for the agencies and businesses engaged in post-earthquake housing construction.

Everyone agrees the Expo was a failure. Few visited the site and fewer still chose one of the model homes – many of which were very expensive by Haitian standards – for their project. See HGW #20

“There were some really odd examples,” according to David Odnell, director of the government’s Unit for the Construction of Housing and Public Buildings (UCLBP), one of three government agencies involved with the housing question. “Some of them had nothing to do with the way we Haitians live or think about housing. It was a completely imported thing.”

“There were some really odd examples,” according to David Odnell, director of the government’s Unit for the Construction of Housing and Public Buildings (UCLBP), one of three government agencies involved with the housing question. “Some of them had nothing to do with the way we Haitians live or think about housing. It was a completely imported thing.”

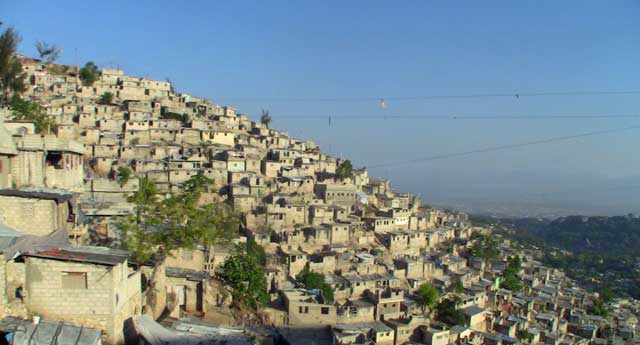

Today, surrounded by weeds and goats, the fading and cracked houses are home to dozens of squatters.

“All the houses have new owners. They have been taken over,” explained a young pregnant girl who said her parents are “renters.”

The young woman who said she was “owner” of the girl’s house sat nearby with a child. Both women wanted to remain anonymous, but she was happy to share her story: “I didn’t follow any procedure got get this. I just took it. My brother was the security guard here. Nobody asked us to pay anything and nobody said anything. And in any case, who would we pay?”

A woman cooking in front of a model house on the Expo site on September 19 2013.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

According to at least four residents as well as a government consultant, the squatters are all people who already lived in Zoranje. Many of the units are now being rented out.

“Yes, that’s possible,” Odnell, an architect, recognized in a November 19 2013 interview. “And you know why. There is a void… and there is no authority there. But [the project] is not exactly a waste. I could call it poor planning, because the houses can always be recuperated.”

Odnell’s counterpart at the government Fund for Social and Economic Assistance agency (FAES), a government office also involved housing, said much the same thing.

“Aside from the inauguration week, the project has been forgotten,” Patrick Anglade explained. “Nobody goes over there because nobody was really managing the project. The entrepreneurs left and nobody promoted the houses. It’s a problem that can be solved, but we have to figure out how to do that.”

The director of the third government housing agency, the Public Enterprise for the Promotion of Social Housing (EPPLS), had little to say. (“Social housing” is known as “subsidized” or “public” housing in English.)

“We have nothing to do with that,” director Miaud Thys told HGW.

Anarchy Reigns in the House(s) of Chavez

Another new project sits practically across the street from the Expo: 128 apartments built by the Venezuelan government for US$ 4.9 million (according to its figures) during the Hugo Chavez presidency. They are usually called “Kay Chavez yo” – “The Chavez Houses.”

Earthquake-resistant, sporting two bedrooms, a bath, a living room and a kitchen, and painted in bright colors, today most of the homes house people who simply broke down the doors and moved in. Only 42 of the 128 have “legal” inhabitants: families invited by the Venezuelan Embassy. Empty for 15 months, some were vandalized. Fixtures, toilets, sinks and other items, including water pumps, were stolen. See HGW #12

“Nobody is in control over there. People just seized the homes,” Thys admitted to HGW. “We know that. Now we are trying to recuperate them.”

One of the houses at the project build by former Venezuelan President Hugo

Chavez, in the process of being enlarged without any oversight, on

September 19 2013. Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

Inhabitants are already making adjustments: changing some doors, adding windows, building gates and fences.

Surrounded by neighborhood men, Jules Jamlee sits with on a broken chair across the street from a home that is being expanded with the addition of an extra room. Like his friends, he is insistent about his right to “his” home.

“The president knows very well that we are revolutionaries,” he said. “He might make threats but he knows we don’t agree with them.”

Told of the residents’ insistence, Thys had a response: “Revolutionaries or not, we are not going to lose those apartments. We are going to send those people letters and invite them to leave so that we can recuperate them. Today we are starting with the carrot. We’ll use the stick later.”

The housing development still lacks water and residents complain that the lack of adequate water means that the toilets don’t work well. Many residents instead use nearby weedy areas for their physiological needs.

When HGW visited in June 2013, journalists learned that six out of ten residents polled said they walk to get water by bucket. Four said their toilets did not function.

New Owners Not 400% Happy

Known as the 400% or “400 in 100” project because Martelly promised 400 homes would be built in 100 days, the nearby US$ 30 million projec, funded by the Inter-American Development Bank, was inaugurated on February 27 2012. The development has three kilometers of paved streets, a water system (which lacked water until just recently), an electrical system, street lamps and a square with a basketball court.

“Everything was in place so that residents would have all the basic services. In that sense, we proved that in a short time and with minimal funding, we could do well,” Anglade explained in an October 2 2013 interview.

But not all of the new residents are earthquake victims. Many are public administration employees. There was a rush to fill the houses at the beginning. And there are other complications, because the houses are not gifts. Residents must pay a five-year mortgage.

“During the first phase, and because we were in a hurry… we weren’t that choosy. Some people who got housing do not actually have the means to pay for it,” Anglade admitted.

One of the 400% residents coming home with a bucket of water on September 19 2013.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

The mortgages are between US$ 39 and US$ 46 per month. The contract says that “non-payment by the renter/beneficiary for three consecutive months will result in a 5% penalty for each unpaid month” and that “non-payment could lead to expulsion.”

The contract has caused a great deal of grumbling. Dozens of residents complained to journalists.

“The president did not give us a house. He is selling it to us. They are too expensive. What can a person do in this country where there is no work? How can one find 1,500 gourdes (US$ 39) each month?” asked Yves Zéphyr, an unemployed father of two who has lived in the development since November 2012.

The receipt for most recent payment made by the wife of Yves Zéphyr,

on September 19 2013. Zéphyr complained that even though he and others

pay their bills, there is a lack of services. Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

FAES admits it faces a challenge.

“We are not achieving 100% payments, not even 70%,” Anglade said. “At least 30% are behind.”

A small poll by HGW gives an idea of why some people are behind. One-half of ten residents questioned said they are unemployed.

When the project was launched, the government received financing to prepare the land, build the houses, and set up the electricity system, but not for the actual services necessary for a housing development, like water, septic system cleaning, a marketplace, schools, a clinic and affordable transportation to downtown.

“We have space for all the necessary services,” explained the UCLBP’s Odnell. “They were all in the initial plan, but we couldn’t achieve all of them. In the end, we could only build the houses. We were only able to put in the water recently, once we looked for and got the necessary financing.”

While many residents say they are happy with their new homes, HGW found problems. Some roofs leaked every time it rained, and residents said that electricity was very rare. Some of the houses had been vandalized before residents moved in: tin roofs and toilets had disappeared.

Also, the septic systems for some of the houses are causing problems.

The unused toilet of Yvez Zèphyr on September 19 2013. He said the septic system

is not deep enough. Photo: Photo : HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

“They fill up in a quarter of an hour!” claimed André Paul, who has lived in “400%” since July 2013. “Some of them are completely blocked, others are just totally filled.”

EPPLS, which shares responsibility with the FAES for the site, recognizes that the septic systems were “poorly built.”

“We will correct them,” Thys promised.

“The project isn’t finished yet,” Odnell noted. “The government needs to continue working, in order to improve the lives of the people there. Normally when you plan a housing development, all of the services are supposed to be in place and the houses come at the end. But just the opposite happened with the 400% development.”

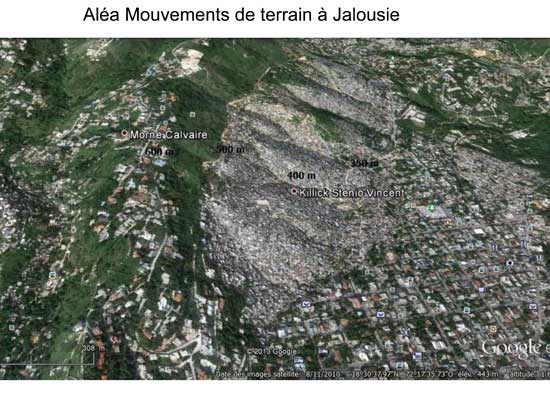

Is Morne à Cabri a Public Housing Project?

The Lumane Casimir Village project was financed with US$ 49 million from the Petro-Caribe fund, according to the government. Named after a famous Haitian singer, the rows of homes sit in the desert-like plain at the foot of Morne à Cabri and will eventyally have 3,000 rental units. About 1,300 are ready. See also HGW #19

During the May 16 2013 inauguration, the president handed out keys to a group of families that had been assembled for the media. But they did not move in. From May to September, nobody actually lived in the apartments. Families only moved in starting in October. In the meantime, many were looted.

“Between 120 and 150 apartments were vandalized,” the UCLBP’s Odnell admitted. UCLBP is the supervisor of the site.

More than 50 toilets, and dozens of locks, windows, brackets, bulbs, electrical cables and outlets were stolen. Many apartments were also damaged by would-be thieves who used crowbars and other tools to try to wrench sinks, doors and windows from walls.

“The thieves still come,” Bélair Paulin told HGW. Paulin spends a lot of time in the area because he is waiting to see if he will be chosen as a renter.

About 200 families have already moved in and others have their keys. Some 1,100 homes remain empty.

Hopeful applicants outside the recruiting office for the Lumane Casimir

Village near Morne à Cabri on September 19 2013. Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

During a visit to the site on December 20 2013, Martelly announced that 250 police officers will be getting apartments and handed over keys to 75 of them, again, in front of the cameras. Several later denounced the fact that they were asked to hand the keys back after the ceremony.

All of the apartments have water and electric systems, new trash cans, a gas stove, a container for receiving and purifying drinking water, plants growing in a garden which will benefit from a regular watering service, and the promise of round-trip transportation to the capital for 20 gourdes (about 50 US cents).

Under the heavy sun, the sounds of the new residents echo though the site. Voices, doors opening and closing, cars coming and going. The village is coming to life.

A man walks through Lumane Casimir Village on September 19 2013.

Photo: HGW/Marc Schindler Saint-Val

According to Odnell, eventually the village will have “a waste disposal system, a police station, a health center, a drinking water reservoir, a public square, a soccer field, a connection with the electricity system, a vocational school, an elementary school and a marketplace.”

The government is also building an industrial park across the street, where – authorities hope – residents can work.

“The mini-industrial park will have all the facilities necessary to create local jobs for housing beneficiaries,” Odnell promised, noting that a Canadian company has already expressed interest.

The park is not yet finished and – as of late 2013 – has not yet been registered as a “free trade zone” park.

Like other projects, the new residents of Lumane Casimir Village are not necessarily for earthquake victims.

“There are three criteria for being eligible: 1) You have to have been affected by the earthquake, 2) the person has to have a family of not more than 3-5 people, and 3) the person must have a revenue. That is the most important, so you can pay your rent, which will be between US$ 163 and US$ 233 per month,” according to Odnell.

Christela Blaise is one of the new renters. A cosmetician, she has lived at the village with her older sister and baby since October.

“After the earthquake, we lived in Bon Repos on the main highway. We were not direct victims of the earthquake, but like everyone who was looking for a place to live, we got a temporary shelter. But that didn’t last past three months, so we moved back to our home,” she said.

Housing: An immense challenge

The Haitian government recognizes that it faces an enormous challenge. Some 150,000 earthquake victims still live in about 300 camps and another 50,000 live in the new sprawling slums Canaan, Onaville and Jerusalem. Half of the camps have no sanitation services and only 8% are supplied with water, according to an October 2013 report from the UCLBP and the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM)/Shelter Cluster. Residents of over 100 camps are in imminent danger of being evicted. In December, 126 families were forced to leave their homes and shacks in Canaan, near Village Lumane Casimir.

According to the government, the housing deficit will only continue to grow as people leave the countryside and smaller towns and move to cities.

“Haiti needs to meet the challenge of constructing 500,000 new homes in order to meet the current and housing deficit between now and 2020,” according to the UCLBP’s new Policy of Housing and Urban Planning (PNLH), released in October.

Image from the UCLBP’s new Policy of Housing and Urban Planning (PNLH).

The new policy is ambitious but vague. The Executive Summary sketches out five “strategic axes” that will help “grow access to housing,” including “social housing” that meets construction norms, and through the promotion of “models of housing that assure access to basic services.”

The language of the document implies that the government will seek to resolve the deficit in partnership with the private sector. In the introduction to the PNLH, for example, Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe notes that “under the coordination of the UCLBP, the PNLH also makes clear the important role that the private sector is being called upon to play, side-by-side with the state.”

While this kind of orientation should not necessarily be rejected out of hand, already with the Lumane Casimir Village and the 400% and Chavez Houses projects, it appears that the government is no longer going to build social housing that is within reach of the majority of Haitians.

According to the World Bank, 80% of the population lives with a revenue of less than US$ 2 per day. Even if a couple combines its revenues, it would have only about US$ 60 a month. How could that family pay a rent that runs from US$ 39 all the way up to US$ 233 per month?

Speaking about the Lumane Casimir Village on November 11 2013, Lamothe affirmed his pride in the project, which he called “social housing.”

But, if the housing is not for the poor – such as, for example, the majority of the earthquake victims – and if, with monthly rents that reach US$ 233, it is out of reach of 80% of the population, is it really correct to call it “social" or public housing?

Haiti Grassroots Watch - Ayiti Kale Je | Comments Off |

Haiti Grassroots Watch - Ayiti Kale Je | Comments Off |