World Bank "success" undermines Haitian democracy

part 3 of 3

Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dec. 20 – A $61 million dollar, eight-year World Bank community development project implemented across half of Haiti has successfully repaired roads, built schools and distributed livestock. At the same time, however, the Project for Participatory Community Development (PRODEP) – Projet de développement communautaire participatif, has also helped undermine an already weak state, damaged Haiti’s “social tissue,” carried out what could be called “social and political reengineering,” raised questions of waste and corruption and contributed to Haiti’s growing status as an “NGO Republic” by creating new non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Although Haiti Grassroots Watch’s extensive fieldwork was concentrated in the Southeast, a report by two World Bank economists supports the idea that the findings can be extrapolated.

In their articles and a new book – Localizing Development – Does Participation Work? – Ghazali Mansuri and Vijayendra Rao found that many “Community Driven Development” or CDD projects tend to benefit the “wealthier, more educated” participants who are “often more politically connected” and who “tend to make decisions in community meetings.” [See stories 1 and 2]

Thanks to PRODEP, Haiti’s “failed state” fails again

One of the most questionable outcomes of the PRODEP system is what appears to be a deliberate undermining of Haiti’s “failed” state.

For decades, development and emergency funding has mostly bypassed the Haitian state, which many foreign governments and agencies dismissed as corrupt and inefficient. There were and still are internal reasons for Haiti’s poorly run government institutions. But, as Oxfam Senior Policy Advisor Angela Bruce Raeburn recently wrote, “Understanding how the US and other international donors have bypassed the Haitian government in the past is key to understanding” Haiti’s weak state of the present.

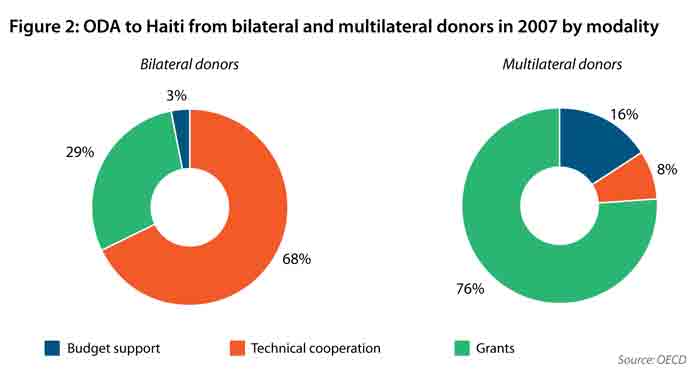

A 2011 study from the UN Office of the Special Envoy showed that in 2007, for example, only three percent of bilateral aid, and 16 percent of multilateral aid, was “budget support,” meaning support for government ministries and programs, including communal section elected officials and their budgets.

Analysis of ODA (Overseas Development Aid) to Haiti in 2007. Bilateral donors

gave only 3 percent to support the government's budget, while multilateral's

gave only 16 percent.

The document states, however, that the most effective way for aid to strengthen public institutions is by channeling through them. However in Haiti “most aid is still channeled in the form of grants directly to international multilateral agencies, and non-state service providers (NGOs and private contractors).”

Deputy Special Envoy Dr. Paul Farmer prefaced the report by noting that “creating jobs and supporting the government” is key to ensuring “access to basic services.” He called on donors “directly invest in the Haitian people and their public and private institutions. The Haitian proverb sak vide pa kanpe – “an empty sack cannot stand” – applies here. To revitalize Haitian institutions, we must channel money through them.”

“Community driven development” (CDD) projects like PRODEP also work better when they work with local governments, according to World Bank economists Mansuri and Rao. But the PRODEP program deliberately channeled its funding almost exclusively to non-state service providers: the agencies CECI and PADF, and the so-called community based organizations or CBOs. [see Story 1]

What might have made more sense was to bolster Haiti’s local rural governments – the CASEC (Conseil d’administration de section communale or Communal Section Administrative Council – whose budgets pale in comparison.

Empty CASEC office in Anba Grigri.

In 2008, six CBOs in Anba Grigri received nearly $100,000 altogether, while the local CASEC had only about $6,500 for the entire year – to building a “community center,” repair a road, or host the town’s annual celebration.

Construction of a parallel government?

Even before PRODEP began, the World Bank and other donors called for the creation of organizations to “facilitate… rapid impact” decentralized “interventions” outside of local government structures. [see Story 1]

PRODEP accomplished this by working with existing CBOs and by helping create new ones, and then by offering training and support to create COPRODEP council, for which the World Bank and PRODEP implementers had even more in mind.

“The goal is for the COPRODEP to mature from a project-specific tool into a locally driven self-sustaining community institution, managing funds from multiple sources and supporting the institutional capacity of local public institutions,” according to 2010 World Bank document justifying $15 million in additional PRODEP funding.

COPRODEPS are today called CADECs” (Conseils d’Appui de Développement Communautaire or Councils to Support Community Development). PADF and CECI have been contracted to help the CADECs “in becoming independent non-profit associations that may later develop into Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) with the capacity to support local public institutions, projects, and programs,” according to the World Bank document. Local elected officials and “notables” are invited to sit on the councils, but 80 percent of seats go to CBOs.

“It’s a little revolution taking place at the departmental level today,” explained Arsel Jerome, who heads up PRODEP in the five geographic departments where PADF ran the program.

“The big challenge for us is to institutionalize PRODEP and for the CADECs to become permanent local structures that run all local community development activities.”

What could be seen as a decentralization of “The Republic of NGOs” has only reached about half of Haiti’s 140 communes, but PRODEP officials recently said they are seeking $100 million to fund a nationwide PRODEP 2.

Harm to the grassroots?

In addition to undermining local authorities, PRODEP’s method also appears to have hurt local grassroots organizations and what the World Bank economists call “organic” or “endogenous” participation, the kind of organizing and participation that drives social movements.

Elace Dirou, a farmer and member of Kòdinasyon Oganizasyon Bene (KOB) or Coordination of Bainet Organizations, lamented that “when these projects come into our communities, they actually destroy organizations. They make people become enemies. People that used to share what little they had – salt, matches, etc. – now turn their backs.

Elace Dirou.

Dirou said that KOB – founded in 1990, during the euphoric days of the democratic and popular movement – abstained from participating in PRODEP when it realized the social and political reengineering that could result from the project.

Anthropologist Mark Schuller has been documenting such societal changes since 2001.

Professor at the Northern Illinois University as well as the State University of Haiti, and author of the recently published Killing With Kindness – Haiti, International Aid and NGOs, Schuller said, “ With the influx of NGOs and projects, people lose their sense of solidarity, of working together. I think this is one of the most direct effects NGOs have had here. NGOs are based on contracts, on money, on ‘what can you do for me?”

“Because foreigners are the ones helping, after a while, people even cease to believe in Haitians! They say ‘Haitians can’t do anything’ because the NGO is doing all the work in their neighborhood… It has a direct impact on peoples relationship with one another, with how they work together.”

While PRODEP documents and officials claim the program aimed to “improv[e] community governance and build social capital,” the World Bank economists who surveyed CDD projects worldwide said that was nearly impossible.

In their June 2012 paper “Can Participation Be Induced? Some Evidence from Developing Countries,” Mansuri and Rao concluded “the idea that all communities have a ready stock of ‘social capital’ that can simply be harnessed is naïve in the extreme.” They also note, in a paper a year earlier, that “participation [in CDD projects] has little effect on the exercise of voice or on community organized collective action outside the participatory structure. Instead, some evidence points to a decline in collective activities outside the needs of the project.”

“Induced participation” is not the same as homegrown. Organizations that “arise endogenously” are part of social movements, while “induced” ones tend to organize because they are seeking “cash and other material payoffs,” the authors note.

Anba Grigri saw the birth of a number of new so-called CBOs.

“Yes, there are a lot of organizations created because of what PADF is doing. They are waiting for PADF to fund them,” according to Jean Louis Nicolas, a local elected official.

CASEC Jean Louis Nicolas.

Schuller has noted the same phenomenon in Haiti’s capital.

“There are a lot of organizations founded to channel funding from ‘NGOs,’” he said. “You could call those organizations ‘fake’’ or maybe ‘pocket organizations,’ because they have a piece of paper in their pocket that says they are an organization, but for the majority of the population, they don’t really exist.”

“Elite Capture”

One final negative effect noted in the Southeast as well as by Mansuri and Rao is that the people and organizations that tend to benefit the most in CDD projects in poor countries are those who enjoy privilege and power at the local level. This phenomenon is known as “elite capture,” and was listed as a risk in early PRODEP documents.

Mansuri and Rao’s survey found that in poor countries, “[a] few wealthy, and often politically connected, men – who are not necessarily more educated than other participants – tend to make decisions at community meetings.”

Like many others in and around Bainet, François Brunel, a member of OJDB (Oganizasyon Jen pou Devlòpman Bene or Organization of Bainet Youth for Development), voiced concerns that the projects and their benefits were being used to further political careers. Brunel said CBOs that won the approval of the council were those that “were in the same political group” as powerful council members.

“They made their choices with elections [inside the council], but in those elections, if you weren’t a good ‘partner’ of the council members, your project would not be chosen,” he said.

Those whose projects were funded voiced similar concerns. The corn mill employee, Fabien Jean André Paul, told HGW that organizations “had to do a kind of campaign” to make sure they got the votes they needed in order to receive their funding.

A “successful approach”?

According to Mansuri and Rao, over the past decade the World Bank has spent some $80 billion dollars on CDDs and participatory development projects worldwide. At least $61 million was spent in Haiti.

Was it and is it a success?

Yes, according to its stated objectives. According World Bank documents posted online, the projects built or rehabilitated 785 kilometers of road, 444 water distribution points and 448 classrooms, and also contributed to building or stocking other community services like health clinics.

But what about the 20-30 percent of the projects which failed? Where did the $6 million in funding money go?

More than half of PRODEP’s $61 million – some $32 million dollars – went to the agencies overseeing the project. How was that money used?

Even if the creation of new CBOs was an objective, don’t these “induced” organizations harm Haiti’s social tissue and the existing grassroots groups?

And isn’t it likely that the monetization of community work and of relationships has a negative effect, as the World Bank economists and anthropologists have claimed?

Finally, will the construction of a parallel state, a “permanent local development structure” dependent on foreign aid, contribute to Haiti’s economic development and transition to democracy?

Return to Introduction and video

Haiti Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA), community radio stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media and students from the Journalism Laboratory at the State University of Haiti.